By Ian Carr with the help of Louis Fernandez. Originally posted on bikehouse.org

Intro

So you’ve decided you want to spend some money on a bicycle. You’re done riding the bicycle your uncle wasn’t using anymore and supposedly raced in college. It’s time to invest in something more suited to your needs. Congratulations! You’ve made a great decision.

So, what type of bike should you buy? I get this question a lot so I wanted to put together some good advice that should inform anyone’s first big bicycle purchase.

If, instead, you’re looking to just buy your very first bicycle and test the waters, see our Guide to buying a used bicycle. It’s tailored more toward those at the very beginning. The advice and information here will be useful to you at some point, but this is tailored for someone who knows they will ride their bike frequently and wants to make an investment.

I’ve tried to be as impartial as I can. Some of the advice is dogmatic, but I think that’s useful for a beginner.

So you know where I’m coming from, I’m Ian. I’ve been into bikes for as long as I

can remember. I’ve been a mechanic at a few shops over the course of about 7

years. I’ve raced mountain, road, and cyclocross. Bikes have also been my primary

form of transportation for my whole adult life. I’ve gone on several self-supported

tours, on the road and off. I’ve been heavily involved with a DC bike coop called the

Bike House for the last several years. And I recently started helping out here at

Mechanical Gardens.

There are a lot of kinds of bikes and riding, but a handful of principles and rules cut across all of them. So whatever kind of bike you want your first adult bicycle to be, these ideas should be helpful.

Nomenclature

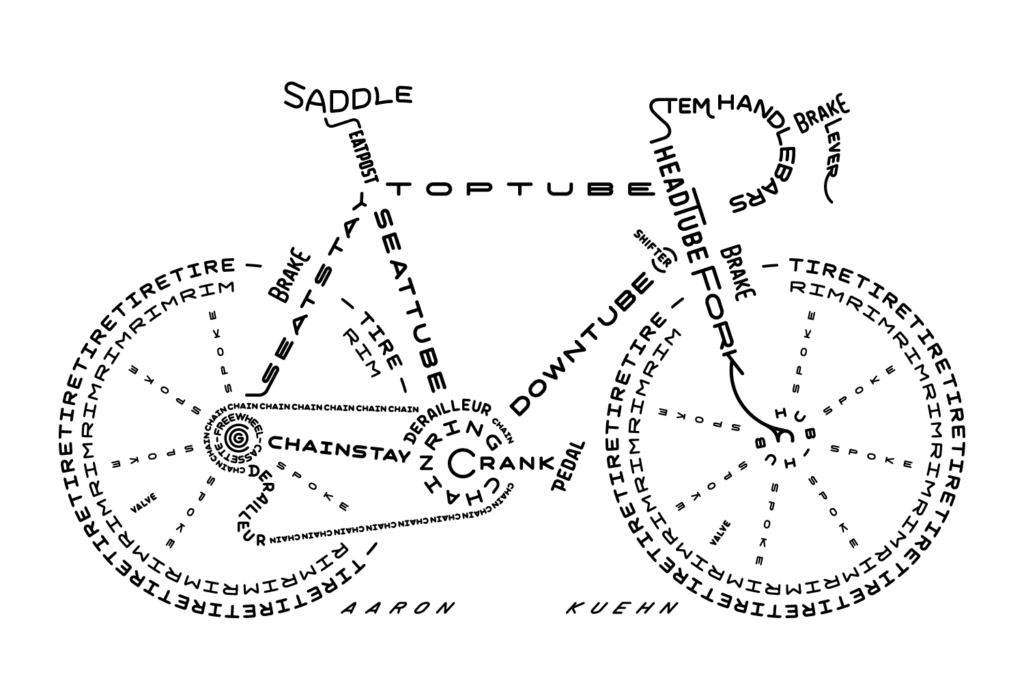

Use the great typogram by Aaron Kuehn for names of parts of the bike. The nomenclature is useful and worth learning.

Fit

First and foremost, your bicycle should fit you. There are many types of bicycle each with its own fit philosophy and guidelines. You’ll never find a bicycle that will 100% fit you off the rack. Making adjustments and swapping components will always be required to get your bicycle to fit you properly. The process can take some time and some trial and error, and will change over time with your fitness, flexibility, and experience.

The important thing is to find a bike that roughly fits you by its static dimensions, i.e. the frame size and wheel size.

Most people are accustomed to sizing used in department store bikes, “S, M, L, XL”. These bikes are toys, generally inexpensive, imprecise, and not intended to be used seriously or for very long. Because of this, the sizing of the bikes can be coarse.

Frame manufacturers generally increment size by 1 or 2cm. For road bikes, you will typically see sizes like 52, 54, 56cm etc. This dimension refers to the length of the seat tube. While seat tube length is used to indicate frame size, it is not the most important dimension.

The most important dimension is the top tube length, as measured from the center of the seat tube to the center of the head tube. This is a static dimension of the bike and needs to be within the correct range for your bicycle to fit you. Fine tuning can be done with saddle positioning, stem length, and handlebar style, but you should think of those as small adjustments. They can’t make up for a frame that is the wrong size to begin with.

For example, on a road bike which I intend to ride fast, I’ve found that a 54cm top tube, 90mm stem, and shallow, low reach drop bars works well for me. It took me a long time to find that combination.

Each person and type of riding requires different considerations. It’s extremely helpful to go to a local bike shop and test ride several bikes in the category you’re shopping for. I would recommend riding them for some time, not 5 minutes around the parking lot, but 20-30 minutes if you can.

Use

The old joke goes that the correct number of bikes to have is N+1 (where N is the number of bikes you currently own). After this first big bike purchase, I imagine you’ll find yourself wanting a more diverse group of bikes for more diverse uses. I myself peaked at 6 bikes just for me. They all had different purposes and it was a joy to have such specificity and choice in what I’d ride in what situation. Since then my collection shrunk, and my remaining bikes have each taken on more uses. Until you diversify your collection of bikes, you’ll need to consider what uses you want your first big purchase to fulfill.

This first bike of yours will probably have many jobs. Like cars, when you emphasize one use-case others will suffer – a two-seat convertible sports car is fun but isn’t much help when you want to move some lumber (or anything else). The key is to decide on what use cases are most important and understand that one bike won’t be able to do all of them.

The typical spectrum of uses cases runs from technical mountain singletrack or downhill riding all the way to a track bike only designed to be ridden on a wooden velodrome. These days there’s a lot of granularity between those two poles. While it used to be that you had road and mountain bikes, now you have gravel, adventure, and cyclocross-type bikes that blur those lines considerably. These bikes in the middle of the spectrum are versatile, but can’t do everything. Think of them as a jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none situation. If you want to ride singletrack buy a mountain bike, if you want to ride on the road with the fast, spandex-clad groups, buy a road bike. Both of those will still be better at their respective jobs than the gravel/whatever bikes in the middle.

Commuter + X

For this first bike purchase you will most likely want “commuter + X” bike, a bike that will work well as a commuter but also allows you to do something else too.

Commuter + Tourer

For example, a combination I see a lot, a commuter bike that also allows some overnight camping trips. Luckily this combination shares a lot of characteristics: durability, loading capacity, comfort focus, all-weather usage. Something like the Surly Straggler is a very common choice for commuting and light touring and for good reason! It has lots of mounting points for racks and fenders, has room for big tires, is made of steel (more on materials later).

Commuter + Road

If instead, you wanted to commute and do a triathlon or road race… this combination is a bit more difficult. The lightness and performance focus of a road bike does not lend itself to the battering an everyday commuting bike gets. That being said, plenty of people commute on road bikes just fine and you can too! A modern road bike, not a tri bike, would be a great option – something like the Cannondale CAAD12 or Specialized Allez. You’ll be able to ride it fast with groups, put some locking skewers on there and commute with a backpack.

Commuter + Mountain

Say you want to commute but also do some singletrack riding on the weekend. This combination is pretty easy too. Mountain bikes are tough, a great characteristic for a commuter. There are several modern mountain bikes with rack mounts for touring, look at the Surly Bridge Club (or really any of their mountain bikes). It will be slower on the road for your commute but give you the combination of uses you’re looking for.

If you’re not looking for a combination of anything and you just want to ride road? That’s the easiest of all, get a road bike! You get the idea.

So consider what uses you’d have for the bike. Is it just transportation? Is it for long tours? Is it for racing or riding with fast groups? The minutia of your specific uses can really inform what bike would be best.

Materials

Bikes are generally made from 3 materials: steel, aluminum, and carbon fiber. The choice of material entirely depends on your use case. No material is wholly better than others. You might be thinking “Lighter is better and aluminum and carbon fiber bikes are lighter so I should get one of those!” But not so fast! There are upsides to each of the material choices that I’ll briefly go over.

Steel

By far the most common material to make a bicycle frame out of and for good reason! Steel bikes are generally robust, can be dented without failing, and ride really well. Steel bikes can have the longest life of any frame material if they’re used and stored with care.

The classic description is that steel flexes and can absorb some road vibration. While that depends on frame quality and design, it’s generally true. The other common association with steel bikes is that they’re heavy. This also has some truth to it. Steel is a denser, heavier material than aluminum and carbon. That being said a nice steel bike can be very light, less than 20lbs easily. And in many cases, like commuting or touring, having a light bike is not nearly as important as having a reliable, robust bike.

In fact, all of my current bikes are steel. When reliability, longevity, and quality of ride are your objectives steel is the material you want.

Aluminum

Aluminum is a funny in-between material in bicycle frame manufacturing. It can offer a sporty, relatively high performance frame for little money. Aluminum has a lot to offer in some use cases.

When I was racing road in college I had very little money but wanted a purebred road racing bike. The frame material of choice in that case is aluminum (A Cannondale CAAD9 at the time). It’s light weight and stiffness (for more efficient power transfer from leg to wheel) combined with the low price made it the perfect material for an inexpensive racing bike.

This idea extends to mountain bikes as well. If you want a fun, light, inexpensive trail riding bike an aluminum hardtail (meaning only front suspension) is your best bet. In fact, the larger tires and suspension of a mountain bike can make up for the sometimes harsh ride aluminum frames offer.

If your interests lie with fast roadie groups or technical trails, rather than commuting or touring, an aluminum road bike with a carbon fork or a aluminum hardtail are great options.

Carbon Fiber

In general, if this is your first adult bike, I would not suggest getting something made from carbon fiber. Assuming you have a limited budget, even if there’s a carbon bike you can afford I would definitely advise you not to buy it. The manufacturing process for carbon is complex, and the companies offering very cheap carbon bikes inevitably cut corners somewhere. These cheap carbon bikes are notorious for failing in short order.

If, for some reason, your budget for your first adult bike is very large (multiple thousands of dollars (which it should not be)) and you want something very high-end, by all means go for a carbon bike. It is the highest performance, lightest, best riding, most expensive material in most cases. For a multi-use commuting bike it’s not a great material. It can crack if dropped on something sharp, and unlike a steel bike, it cannot be easily repaired.

Groups & Compatibility

An aspect of bicycles that can be intimidating to a new rider is parts variety and compatibility. There are three large component manufacturers: Shimano, SRAM, and Campagnolo. Several smaller companies have come onto the scene in recent years as well. Unfortunately, living in a golden age of bike parts, as we are, means lots of options and lots of industry “standards”. It can be daunting.

Each of the component manufacturers have tiered component lines. Take Shimano road groups as an example (group or gruppo refers to a collection of components designed to work with one another). Shimano road groups in ascending order are: no name plastic stuff, Sora, Tiagra, 105, Ultegra, and Dura-Ace. Mountain and commuter groups have their own tiers. I know it feels like a lot, cause it is, but it’s something to be aware of.

In general, if you’re planning on riding your bike a lot, I would suggest steering clear of the lowest end stuff. For the Shimano road group lineup for example, the middle of the road group, 105, is a sweet spot. It’s typically designed the same way as the higher end groups (Ultegra and Dura-Ace) but uses steel in place of titanium or carbon fiber – i.e. heavier, less expensive, but still good. Modern Tiagra is also very nice.

It’s hard to give general advice on this because there’s so many versions and options, but the advice I want to drive home is to avoid the absolute lowest end. For this first adult bike, assuming you plan to ride it a lot for a long time, somewhere in the middle of most tiered group lineups should be what you’re aiming for.

Some other examples of mid-tier groups are:

Road

- SRAM Apex or Rival

- Shimano Tiagra or 105

- Campagnolo Centaur

Mountain

- Shimano Deore or SLX

- SRAM NX or GX

Along these lines, you’ll find that many companies have proprietary designs which are only compatible with their other components. There are also industry-wide standards and some companies (Surly again) do a good job of fitting their bikes with these types of standardized components.

If you’re not sure what new component will be compatible with your current stuff,

stick with components from the same group of the same age. If you want to branch

out, this is a great opportunity to talk to your local bike shop or us here at

Mechanical Gardens. Parts compatibility, especially in the drivetrain, can be one of

the most confounding aspects of bikes when you’re first getting into it.

Conclusions

This may seem like a lot, but it’s a really fun process. Take your time, do some

reading on forums and places like SheldonBrown.com, and of course talk to the

knowledgeable folks from Mechanical Gardens. We’re always happy to chat about

bikes. There are a lot of snobs out there so take any advice (including mine!) with a

grain of salt. There’s a lot of room for self expression when putting together a bike,

so get the stuff you like! It doesn’t have to be the best of the best, just enjoy

yourself and be safe.

If you have any questions for us, reach out! Come to open hours

at Mechanical Gardens! We’re here to help you learn.

By Ian Carr

March 2020